Macedonio Melloni. Il calore e la luce invisibile

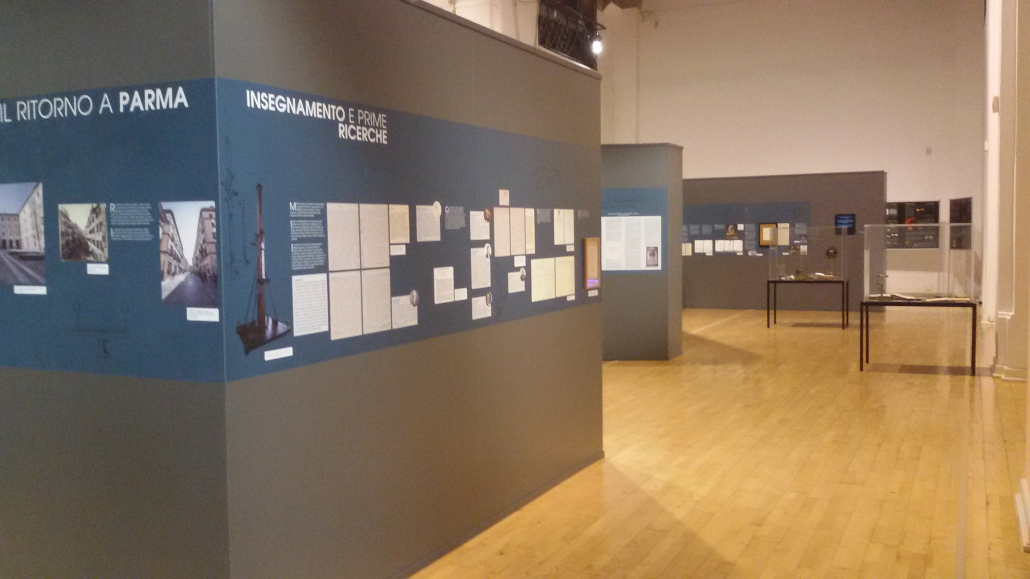

18 April/7 June 2015

Gallery San Ludovico – Borgo del Parmigianino 2/B, Parma

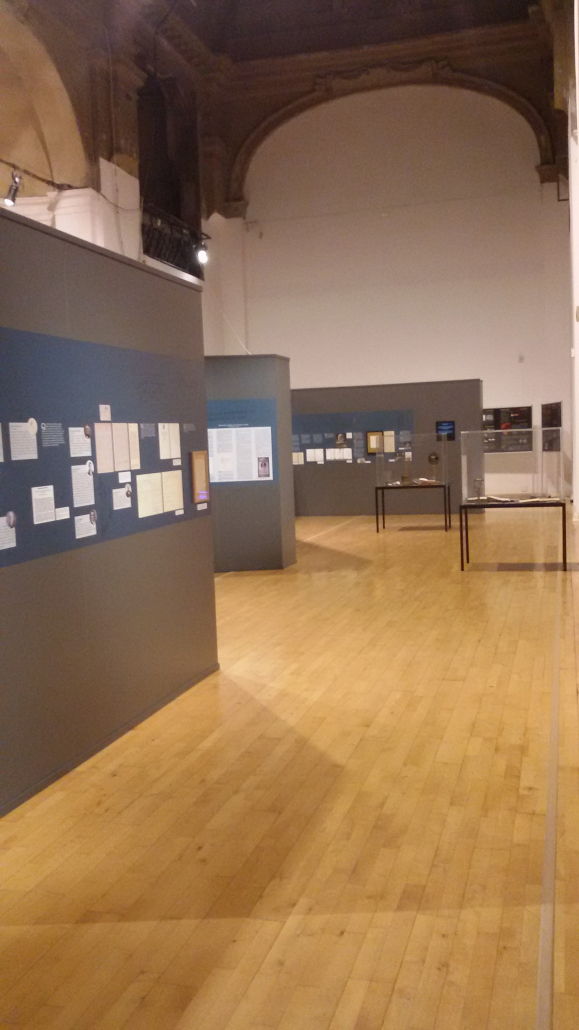

The exhibition aims to retrace and present the main stages of Macedonio Melloni’s (Parma 1798 – Portici 1854) life and activities as a scientist and patriot, presenting his pioneering research activities, his relations with leading contemporary scientists, his fervent intellectual activity and the political passion that distinguished him.

The exhibition is divided into different sections that tell the story of the character through images, drawings, letters, documents and scientific instruments that belonged to him, recounting the various phases of an intense life of research, while maintaining a constant reference to the historical and political events of the time.

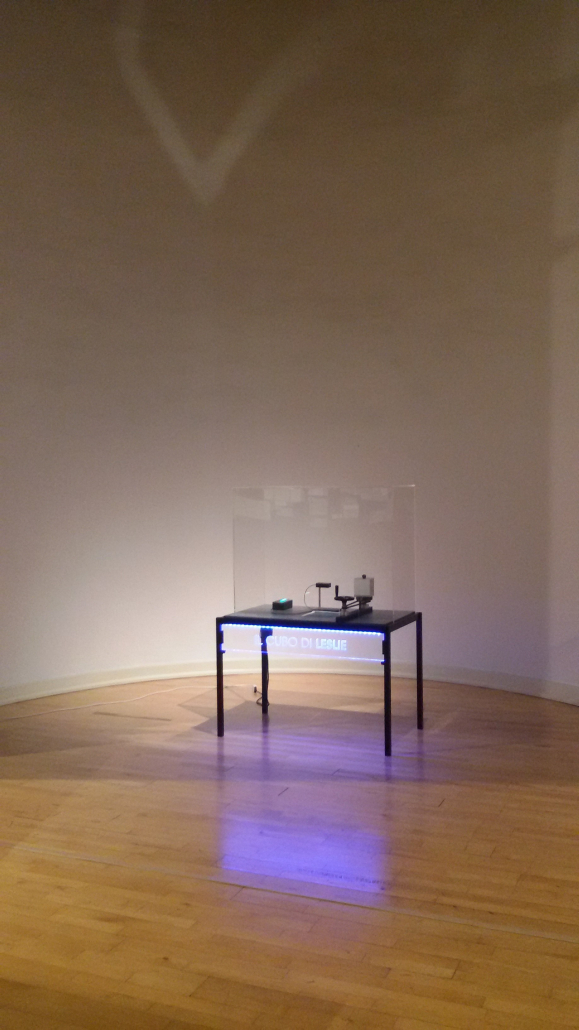

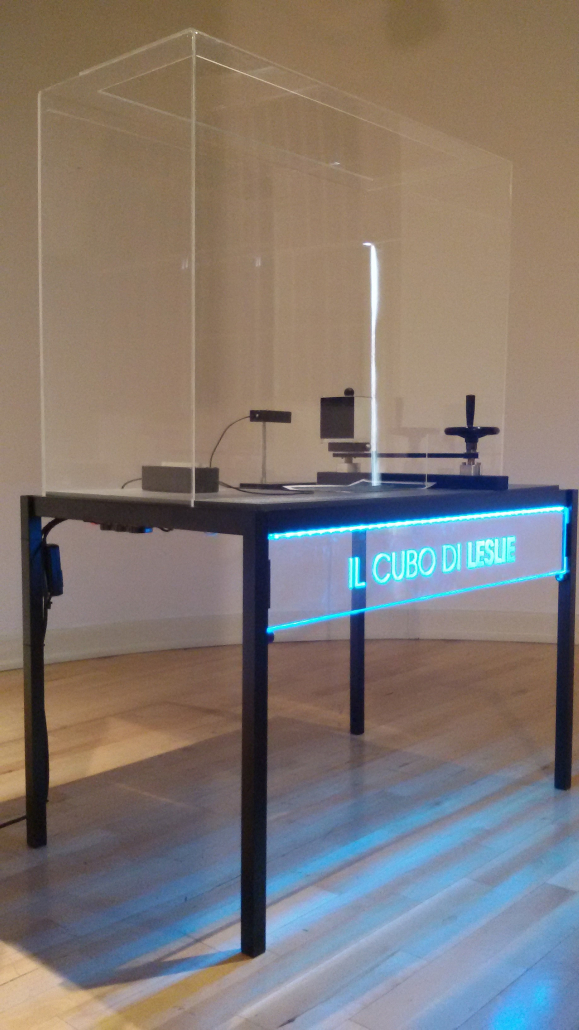

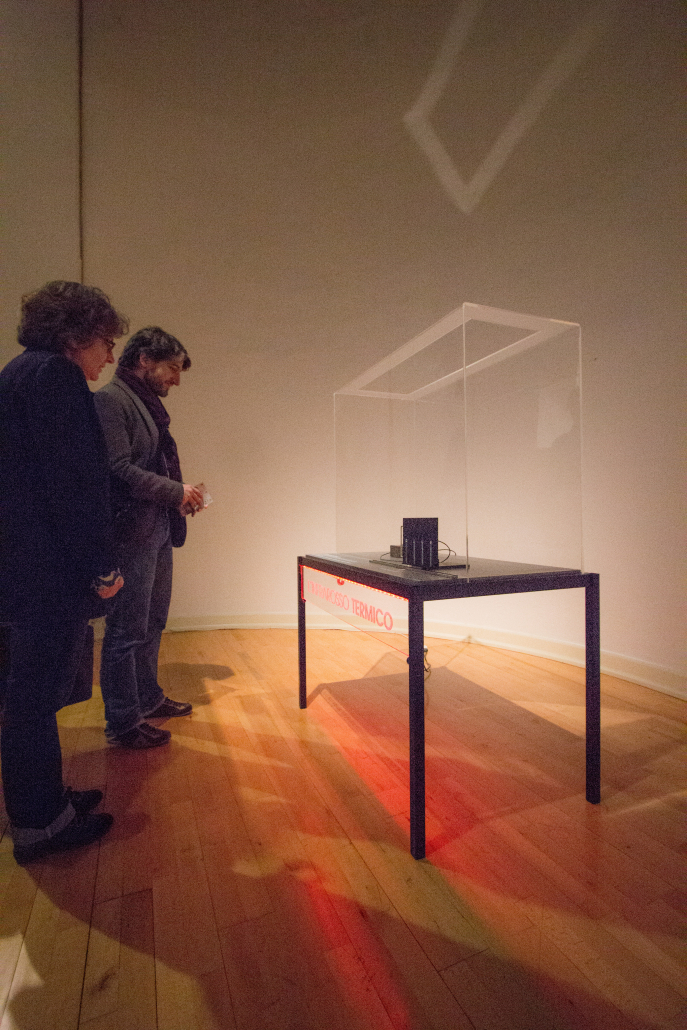

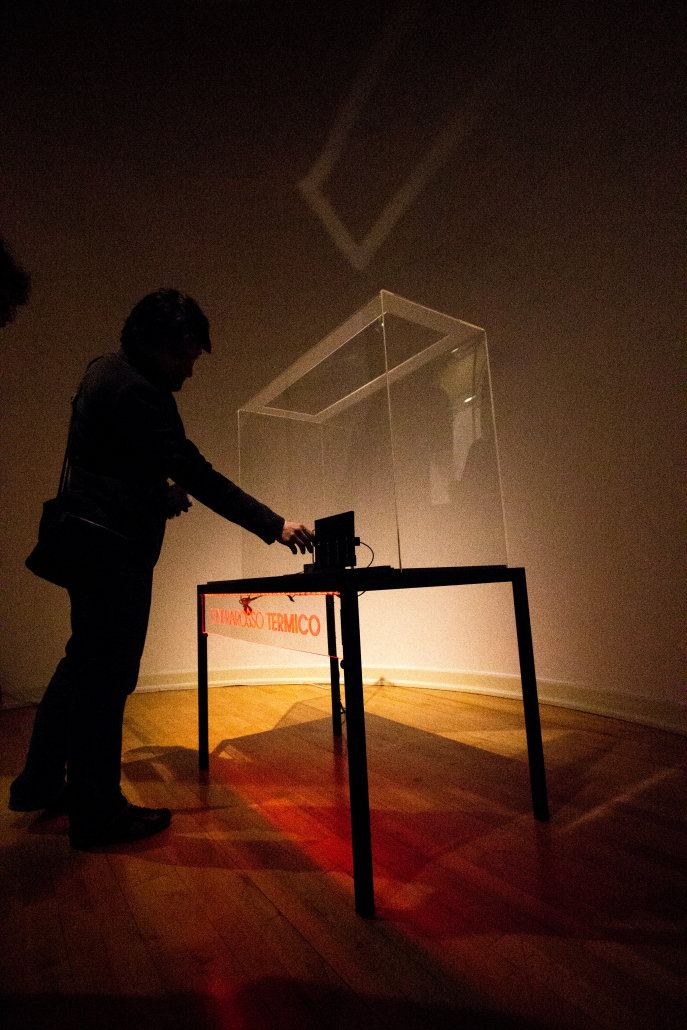

Five interactive stations also allow visitors to simulate first-hand some of the experiments that Melloni himself performed to confirm his theories.

An engaging and stimulating exhibition that seeks to bring the youngest children closer to the study of scientific subjects, delves into Melloni’s life through the presentation of previously unpublished documents, and is an opportunity to learn more about this important personality of Parma.

MACEDONIO MELLONI

Macedonio Melloni was an important Italian physicist who lived in the 19th century.

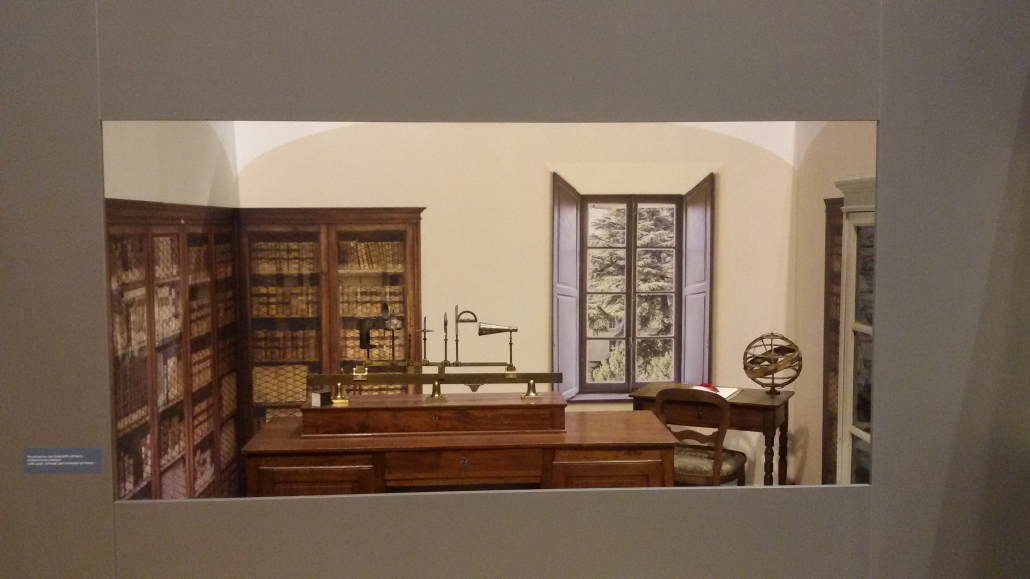

He was born in Parma on 11 April 1798. Having completed his secondary education in his hometown, in 1819 he left for Paris where he attended lectures in mathematics and physics at the École Polytechnique. In 1824 he returned to Parma where he was appointed as an adjunct to the Chair of Theoretical and Practical Physics held by Professor Pietro Sgagnoni. On Sgagnoni’s death in September 1827, he became holder of the Chair and director of the Physics Cabinet. During this period he worked mainly on meteorology and hygrometry and, to his own design, had a series of instruments built for the Physics Cabinet, including a tap barometer. In 1829, he learned that, in nearby Reggio, Leopoldo Nobili had developed an early example of a thermopile, an apparatus based on the thermoelectric effect discovered by Thomas Johann Seebeck in 1821, and he immediately realised the great possibilities of using the new instrument in studies of thermal radiation. When he had already laid the foundations for a series of researches on radiant heat, he was forced to resign and forced into exile in November 1830. His lecture delivered at the opening of the academic year did not please the government of Maria Luigia of Austria, Duchess of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, because there was clear praise for the French students who had largely contributed to the expulsion of King Charles X from Paris in July of the same year.

After leaving Parma, he travelled to Paris and then to Florence and returned there in February 1831 to join the provisional government. He remained there until the beginning of March with the entry of Austrian troops into Parma and the following restoration. Since an arrest warrant had been issued against him, as for other colleagues, professors and patriots, he was wanted as a member of the provisional government. During his wanderings he maintains contact with Nobili, who in turn had to leave Reggio Emilia for Florence following a similar arrest warrant, with whom he has a brief but intense scientific collaboration. The first results are obtained with the thermomultiplier, an apparatus built by combining a thermopile and an astatic galvanometer. Having been offered a teaching post at the University of Dôle in the French Jura by Parisian colleges, including François Arago, he remained there until the beginning of 1832 when he left Dôle for good and settled for a while in Geneva, the guest of Auguste De La Rive, professor of physics at the local university, with whom he formed a friendship that would last a lifetime.

At De La Rive’s laboratory, he was able to carry out the first studies on radiant heat transmission on his own. On 4 February 1833, he presented his results to the Académie des sciences in Paris. In Paris, he assiduously continued his studies on radiant heat transmission, which earned him the Royal Society’s award of the Rumford Medal for scientific merit, the highest honour of the time for physics research on light and heat. Also in Paris, the Académie des sciences appointed a commission comprising François Arago, Jean-Baptiste Biot and Siméon-Denis Poisson, which examined his results in detail and finally gave a highly positive verdict. On 3 August 1835 he had his final consecration by becoming a member of the Académie des sciences, the first in a long series of appointments to scientific institutions throughout Europe. Thanks to the interest of Arago and Alexander von Humboldt, a German naturalist and geographer, who interceded for him with the Prince of Metternich, Maria Luigia revoked his exile decree in 1837.

In 1838, he returned to Parma, but did not stay there for long due to his inability to get a position. He accepted King Ferdinand II of Bourbon’s invitation to move to Naples, where on 18 March 1839 he was appointed director of the erecting Meteorological Observatory, director of the Conservatory of Arts and Crafts and honorary professor of physics. During his speech for the inauguration of the Observatory, which took place in 1845, he outlined an articulate programme of theoretical and experimental research in meteorology and geophysics to be extended to other parts of the `Kingdom, in a broader project of collaboration with France and England. His desire was to create a research centre on the level of other European study centres, in spite of the inefficiencies and hostility of part of the Neapolitan academic environment.

In January 1848, he was forced to resign from all his posts due to his pro-Constitution ideas. He retired to Porticidove where he devoted himself to writing La Thermochrose, a compendium and critical revision of his ideas on thermal radiation. The first part was published in Naples in 1850. The manuscript of the second part, which was not published, was lost along with many documents and apparatuses that belonged to him. During this period, he carried out studies in electrology and experiments on the residual magnetism of lava rocks. He died in Portici, victim of the cholera epidemic, on 11 August 1854.